The Klondike gold rush transformed both Alaska and Canada and the impacts are still felt today. Towns such as Dyea, Skagway, Whitehorse, Carcross, and Dawson City were born; railroads and infrastructure were built; and a global depression – particularly devastating in the U.S. – came to an abrupt end as tons of new found gold (in an economy still based on the gold standard) caused prices to drop and most importantly - the sudden impact of tens of thousands of people spending millions of dollars attempting to reach the gold fields. Talk about a stimulus package. As Gordon Gecko said in the movie Wall Street, “Greed works.”

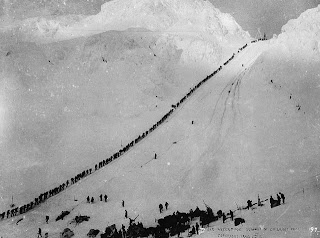

Most of the gold rushers, or “Stampeders,” left the U.S. by boat and sailed from the lower 48 along the Canadian coast, and continued up the inside passage into Southeast Alaska. The boats landed at the end of the Lynn Canal – the longest fiord in North America – and soon two towns were built only a few miles apart, Skagway and Dyea. From there the Stampeders would disembark and begin the daunting trek up the colossal Coast Mountains whose jagged peaks were carved by glaciers not long before. To get over the mountains there were two choices: the White Pass route, beginning in Skagway, or the Chilkoot Pass route, beginning in Dyea. Both were extremely difficult, especially considering the fact that Canadian authorities demanded that anyone entering the country for the gold rush bring enough food and provisions to last an entire year (and weighing about one ton). To enforce this rule, Royal Mounted Police were posted at the mountain summit of each trail (the exact location of the U.S-Canadian boarder had not yet been established) armed with Maxim machine guns and bright red uniforms.

For nearly a year, the greed crazed hordes clambered up the mountains even braving the harsh frigid winter. By 1899, the rush was over and a railroad connecting Dawson City to Skagway was under construction. When the White Pass & Yukon Route Rail Road was complete, Dyea, the town at the foot of the Chilkoot Trail, was deserted in a matter of weeks. In the midst of the Stampeders during the actual gold rush came another group of people – people who still come today for the same reasons: tourists. And it is largely thanks to those people that the towns of Skagway and Dawson City still exist.

Today much of Skagway and the Chilkoot Trail is part of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park – where I work. The 33 mile Chilkoot Trail is jointly managed by the National Park Service and Parks Canada. The trail begins near the Dyea town site. Today, little remains of the once bustling community that for a time rivaled Skagway in size and importance.

Back in August, some fellow NPS employees and I began our own effort to follow in the footsteps of the Stampeeders and climb the infamous Chilkoot Trial. This is our story:

Our plan was to hike the 33 mile trail from Dyea to Bennett in three days and catch the train from Bennett back to Skagway on the third day. Although we were prepared for all possible weather options, we were nevertheless apprehensive at the weekend’s weather forecast of heavy rain and 40 mph gale force winds. Despite the ominous forecast, the morning seemed calm – if somewhat overcast. We began at eight on Saturday morning, August 15. The trail began with a startling climb up a steep slope entitled “Saintly Hill.” The stampeeders reckoned that if you could climb the hill without cursing you must be a saint. We paused at the top of the hill for a moment to remove a layer of clothing or two and continued down the opposite slope. The rest of the hike for the day would be comparatively easy. After pausing at the bottom of the hill we noticed that one of our group – Steve – was missing. We waited for a while then continued on.

Miles later we ran into Steve at Fennigin’s Point. Fennegin’s point was one of the many town sites that developed along the trail. Most of these places were tent cities that provided goods and services to the stampeeders such as hotels, food, alcohol, coffee, women, and other desired comforts. After a quick snack, we continued on to Canyon City.

Canyon City was one of the largest settlements along the trail. Aside from several hotels, restaurants, and other establishments, it boasted electricity thanks to a steam generator built to power a massive cable tramway to help ship gear to the top of the Chilkoot Pass. Today all that remains of the town is the large steam boiler.

After lunch at the Canyon City campsite, we continued on. The trail began to gently climb up the narrow glacier valley and light rain began to fall. We began to notice more and more artifacts along the trail. Once garbage and refuse cast aside from the exhausted stampeeders, the century old junk made the trail “the longest museum in the world.” Soon we were at Sheep Camp – our destination for the night. Sheep Camp was the final resting place before the daunting climb up the “Golden Stairs” and over the pass. It too was once a city. Upon arrival we were graciously welcomed by our fellow NPS coworker – Jeremy.

Jeremy was one of two seasonal trail rangers working in shifts at Sheep Camp. His duties included patrolling the trail to the pass, briefing hikers on trail conditions, responding to emergencies, and serving as the eyes and ears of the park along the trail. Jeremy made room in the modest ranger cabin for our one night stay. For one night at least, we would stay indoors in luxurious comfort while the other hikers pitched tents in the rain. While Jeremy went out to brief the other hikers, we made dinner. Everyone had carried up something to contribute for the meal my contribution were two giant fresh Coho salmon filets. Once Jeremy was back, we feasted on a wide variety of tasty dishes.

At dinner Jeremy gave us an updated forecast – it was worse than before. He advised an early attempt at the pass – as early as we could. He explained that upon learning of the weather conditions, one group of hikers actually turned around and went back. We were unfazed and remained upbeat. The rest of the evening was spent recounting stories of our various NPS careers. Jeremy, however, had the most dramatic stories – harrowing rescues and medevacs (via helicopter) from the trail. After one particularly disturbing story involving a couple of men falling head over heels down the Golden Stairs resulting in broken bones, severe lacerations, and a helicopter ride he added, “but now with the weather conditions there is no way a helicopter could make it up here for days maybe weeks.”

The next morning we rose at 5 am, quickly scarffed down some food and coffee and hit the trail. Before we left, Jeremy had his morning radio call with the Parks Canada folks just over the pass. Jeremy gave us the latest information at the pass, now 60 mph gale force winds and driving rain, but decided not to tell us that the Chief Ranger back in Skagway had chosen to close the trail.

After less than a mile, the forest canopy that had helped cover us from the steady rain gave way to the open rocky alpine. Although the rain continued unrelentingly, the wind and fog were light. Soon we were surrounded by the indescribable beauty of the naked mountains. There were torrents of rivers and streams and large swaths of icy snow. The steep terrain not only rose steadily in altitude, but became increasingly rocky. Several times we were forced to cross mountain streams that had quickly become raging rivers. Soon we were all wet bellow the knee. The wind increased with the altitude and the rain continued without pause. We pushed on in silence.

After several hours, we reached the “Scales.” The “Scales” was the last stopping place before the final climb to the pass over the Golden Stairs. In half a mile the trail shoots up nearly 1000 feet. During the gold rush, the packers would weigh the heavy loads again to charge more for the final push – hence the name “Scales.” In the winter and spring, the Golden Stairs were actually just that – stairs cut into the ice and snow. But in the late summer, with the snow and convenient stairs melted, one must climb over large boulders and rock scree – making the effort even more difficult. Although it is only half a mile, the climb usually takes two to three hours or more.

Following a brief pause, we began the climb separately. We wanted enough space between ourselves in case of a fall. The wind was howling all around as I struggled on my hands and knees over the precipitous rock-strewn slope. There was no trail of any kind to follow, save for a few plastic orange sticks bending at strange angles in the hash wind. The wind, pushing at 60 mph through the narrow mountain pass, continued to increase as I climbed. The rain, driven by the gale force, stung as it pelted my exposed face. The wind would howl at a constant speed for a while then all of a sudden an enormous gust would shove me into the rocks or push me to the side as if some unseen force were tossing me around like a rag doll. My 40 pound pack acted as a sail – either propelling me up or to the side. I began laughing uncontrollably, unable to contain my amazement and joy – totally in awe of the powerful forces of nature at work. I would compare it to one of the greatest roller-coaster rides I have ever ridden. I lost all track of time but eventually ran into Lauren. We paused for a picture and a movie.

I then noticed that Lauren was missing her bright yellow pack cover. I asked her why she had taken it off. “What!?” she exclaimed, obviously not aware that it was gone. But it was gone – ripped off and carried away by the relentless wind. We looked around briefly, but then I yelled over the wind, “Let’s go on - it’s probably halfway through Canada by now!” We pushed on and soon we were at the pass. We again paused for a photo opportunity amid the remains of the old cable tramway and continued on into Canada.

Once at the border, we regrouped inside the tiny Parks Canada staff quarters and were treated to hot coffee and tea. Everyone was exhausted and soaking wet. We stripped off some wet layers of clothing and tried to warm up. It was strange to enter another country without border and customs authorities or any fanfare whatsoever.

The Parks Canada warden cordially invited us to dinner that night at Lindeman City, about 9 miles away. I was ecstatic. While our original plan was to push on to Deep Lake for the night, there were some in our group that were now proposing to stay at the much closer Happy Camp. To be honest, most hikers take this option, but I was dead set against it. Originally, I had argued to push from Sheep Camp all the way to Lindeman City (about 13miles). The Lindeman City campground might provide housing via our Parks Canada counterparts and at the very least enable a relatively short hike out to Bennett the following day. If we stayed at Happy Camp or Deep Lake, our hike out would be longer and stressful – since we had an afternoon train to catch. And, I argued, we could cause a diplomatic incident if we were to turn down a written invitation to dinner. After half an hour, we decided to get moving again undecided of our ultimate objective.

Having crossed the pass, we not only entered Canada, but we were thrust into a completely different ecosystem. The crystal clear alpine lakes, swaths of icy snow, occasional but tenacious plants, rocky terrain, and fog looked as if it were ripped right out of the Lord of the Rings. It was truly amazing. But even though the wind had faded away, the rain did not.

After some miles, our excitement had faded with the wind. Eventually, after a couple hours, we made it to Happy Camp. Like most of the camps, Happy Camp has a warming shelter. We stormed up to the cabin only to find it completely full of people. As the group hesitated at the door, unsure of what to do, I pushed on through and entered the cabin. I was no mood to be polite. I was immediately overwhelmed by the intense humidity and heat of the small one room cabin crammed with people. It was as if I had entered a sauna – a sauna reeking of smelly campers and bad rehydrated food. Some were cooking dinner while others were merely resting from the trail. I saw an open seat and asked if I could sit. The astonished person could only shake his head. I sat down and looked around the room – everyone was staring at me. Unfazed, and ready to play the obnoxious American role, I said in a loud voice, “Howdy, where y’all from?” The group busy cooking dinner began to talk to me. The other half of the people in the room – apparently not eating, began to gather their things and file out the door. To my surprise, none of my compatriots from my group had followed me into the room, but upon seeing the room clearing out, they entered one at a time. I pulled out some food as my group gathered inside. I was preparing to argue against staying at Happy Camp for the night. Most of the group agreed to keep going for Deep Lake but I continued to press for Lindeman City. There was no warming shelter at Deep Lake, I reminded. If we stayed there we would have to pitch tents in the rain. We agreed to postpone a decision yet again and continued on. The next section of the trail – from Happy Camp to Deep Lake was by far the most difficult, not difficult in terms of terrain, but in terms of low morale, exhaustion, and above all continued wetness. Much to the dismay of some in our group, Dash and I pushed to the front of the pack and continued at a quick pace; stopping only long enough to make sure the rest of the group was still behind us. Our goal was to keep everyone moving at a pace fast enough to ensure we would make it to Lindeman that evening. Still, it seemed like the trail would never end.

After many miles, we finally made it to Deep Lake. It was still raining. I was overjoyed, ecstatic, and relieved.

It was still early enough to make it the final three miles to Lindeman City. Once we had regrouped, I posed the question – “On to Lindeman?” To which everyone agreed – some reluctantly so. Several minutes later we were back on the trail. I was motivated only by my desire to be dry and fed. I didn’t stop until I reached Lindeman.

Lindeman City was once a dense settlement teeming with Stampeeders. It, along with Bennett, was the place the Stampeeders stopped walking, built boats and waited for the ice to break up to allow navigation on the Yukon River all the way to Dawson City some 550 miles away. Now, Lindeman City is a Campground and (like our Sheep Camp) the field HQ for Parks Canada trail operations. Every summer Parks Canada erects a small tent city at Lindeman and we were invited to stay with the wardens and treated to an awesome taco dinner. It was heaven. We stayed up late swapping work stories and questions with the Canadians. The Canadian wall tents were pitched on top of wood platforms (reminding me of Boy Scout camp over a dozen years ago) and were both spacious and dry. We might as well have been staying at the Ritz Carlton.

The next morning we had breakfast with the Canadians, and after thanking them gratuitously, left for our final destination – Bennett a mere five miles away. With lots of time before the train, we were able to savor the short hike and stop whenever we felt the need. We paused at the last campground at Bare Loon – it was clearly the most beautiful. Finally we reached Bennett.

Bennett was once a large city teeming with activity and people. Unlike the rest of the cities along the trail, Bennett did not die immediately following the end of the Gold Rush. Thanks to the White Pass & Yukon Route Railroad, Bennett continued to thrive for several years as a port town. People would ship goods up the rail road and transfer them to boat at Bennett. Ultimately, however, Bennett shared the fate of Canyon City, Sheep Camp, and Lindeman and died when the railroad to White Horse was completed. All that remains from the original town is the restored Presbyterian Church.

Upon boarding, I was pleased to find a cooler of beer a buddy that works for White Pass left for me that morning. Everyone on the train was immediately jealous. Most of the people on the train were cruise ship passengers from Skagway on a day long excursion. As trail hikers, we were segregated to our own car in what one passenger aptly titled a “stink vortex.” Almost everyone immediately fell into a deep sleep. The train ride back took nearly four hours to cover 33 miles that had taken us two and a half days. I stayed awake, sipped cold Rainier beer, and savored every moment – it was a suitably relaxing end to another adventure in Alaska.